IN THIS ARTICLE

Introduction Foster a Collaborative Culture Learn the Business Think Full Cost Monitor Plan for the Unpredictable Go Beyond Dollars and Cents The Stakes are High Acting on the Vision Download PDFIntroduction

The recent closures and financial difficulties within Philadelphia’s nonprofit community signal the need for swift action and honest conversation to identify what’s destabilizing these stalwart institutions.

When an organization shuts its doors, it leaves peer nonprofits, funders, and the communities they served asking how and why it experienced insurmountable financial distress, especially if the organization is an experienced and long-standing institution. With each closure, communities lose critical services, jobs, opportunities, knowledge and expertise, and social capital that – when knitted together – are the safety net for the community’s most vulnerable citizens.

These closures also reinforce the critical role and responsibility that leadership teams and boards have in securing the financial health of nonprofit organizations. This is not a time to speculate, point fingers, or assign blame. Instead, nonprofit leaders, board members, and funders must come together with a renewed commitment to financial literacy, transparency, and mission alignment. There is a critical need for stronger governance, fiscal oversight, and collaborative leadership. In September 2024, Nonprofit Finance Fund held a community conversation with 32 nonprofits, funders, and community-based organizations from the greater Philadelphia region to discuss local issues, challenges, and strengths. When attendees were asked about the top challenges facing nonprofits in the region, more than 80% cited an inability to cover the full cost of their organizational needs, and 55% cited a lack of multi-year funding.

This high and widespread level of financial stress is a relatively new development following the pandemic. Nonprofit Finance Fund’s national 2022 State of the Nonprofit Sector Survey found that most organizations that survived the peak of the pandemic emerged in historically strong financial positions.1 But over the last few years, nonprofits and the communities they serve have had to grapple with high inflation and high interest rates, as well as the continuing social and financial fallout from the pandemic. Funding, which rose in the early months of the pandemic, has declined even as community needs have held steady or grown.

Nonprofits are vital partners for government and philanthropy. They support communities’ physical, emotional, and financial well-being; help create jobs that sustain and grow the local economy; and provide education and cultural enrichment. Nonprofits are a lifeline to many and the impact of their services touches us all. The driving force behind these organizations are the leaders who serve, understand, and fight for their communities’ interests, challenge the status quo, and work tirelessly for change.

For social service organizations to make an enduring difference in their communities, they must be financially resilient. Financial resilience begins with strong leadership from the executive team and board, with solid and consistent operational and financial management practices that prepare organizations for unexpected challenges.

By cultivating a culture of transparency, collaboration, and continuous learning, nonprofits can better safeguard their financial health, protect their missions, and sustain the vital services they provide to our communities. The responsibility is shared, and together, executive leadership and board members can rebuild a stronger, more resilient sector.

This report contains six recommendations for how nonprofit leaders and board members can engage in ongoing conversations that will best support their nonprofit’s financial resilience amid chronic systemic challenges and acute crises:

- Foster a Collaborative Culture. Engage in productive conversations about financial health, risk, and opportunity, giving staff time to prepare and address issues.

- Learn the Business. Understand the organization’s financial condition, context, how the business model works, and what metrics are important to monitor.

- Think Full Cost. Discuss how to plan for financial needs beyond the budget, such as reserves, working capital, and facilities.

- Monitor. Review financial health through concise reports that help inform decisions.

- Plan for the Unpredictable. Explore a range of possible outcomes and conditions that might influence financial health.

- Go Beyond Dollars and Cents. Tie decisions and actions back to mission and organizational health.

Financial Challenges

Financial challenges are often greater for nonprofits led by people of color.2 NFF’s 2022 survey found that a staggering 82% of leaders of color reported their organization’s long-term sustainability as a top challenge, while at the same time, 64% saw a significant increase in demand for services.3

Locally, in 2016, the Urban Coalition and Philadelphia African American Leadership Forum commissioned Branch Associates, Inc. to produce a study about Black nonprofit leadership. While the study’s sample size was small (n=16), this first-of-its-kind research found that Black-led nonprofits had fewer cash reserves, were more dependent upon government grants, and were more likely to serve and be in under-resourced Philadelphia neighborhoods than white-led organizations.4 These critical differences leave Black-led nonprofits with less flexibility to invest in organization growth, weather financial uncertainty, and sustain their work.

Foster a Collaborative Culture

Engage in productive conversations about financial health, risk, and opportunity, giving staff time

to prepare and address issues.

Financial resilience requires that a nonprofit’s board and staff maintain open and honest communication. Building the relationships and trust to support such communication takes work.

The dividing line between executive management and board oversight can seem fuzzy, and there is

no shortage of articles about managing either side of the relationship.5 Power, privilege, and personal experience come into play, meaning board members and nonprofit leaders have to navigate relationships, history, and even trauma alongside concrete matters of financial resilience.

There is a reciprocal relationship between executive management and the board – and trust is the currency by which this dynamic thrives or fails. Taking time – and creating opportunities – to build that trust is essential. Open and frequent two-way communication is essential. And trust should be accompanied by transparency, with clear roles and expectations for executive leadership and board members outlined in job descriptions.

Strategies for building a collaborative culture:

- Build trust by getting to know one another. Structure time or activities to understand other’s life experiences and what draws people to the work.

- Get specific. Agree on clearly defined goals, time-bound measurable objectives, specific tasks, and realistic budgets. Staff must provide the right financial information with the right level of detail to promote understanding of the organization’s financial position without getting into the weeds.

- Be explicit about which actions/decisions require board approval versus those that benefit from thought partnership and discussion with the board but will be decided by executive leadership.

- The executive leader and board chair should work together to create a detailed meeting agenda, including difficult topics that need to be discussed, and stick to it. Share it ahead of the meeting so people can prepare.

- Remain curious, ask questions, and prepare to engage fruitfully in difficult conversations around a nonprofit’s finances

- Approach every interaction with care and compassion while exercising accountability for everyone’s respective roles and responsibilities. Provide adequate time for staff to prepare materials and address questions, feedback, or concerns raised by the board.

- Recognize that you’re working together toward a common goal. Orient every meeting or communication between board and senior leadership around this common goal.

“There is a reciprocal relationship between executive management and the board – and trust is the currency by which this dynamic thrives or fails.”

Leaders of Color

Leaders of color face unique struggles in their relationships with their boards. The relationship between the board and leaders of color – especially women of color – can be especially fraught.6 Studies have shown that executive directors of color receive less support from their boards and are significantly less likely to report good communication with their boards than their white counterparts. Leaders of color feel less trusted by their boards than their white counterparts, especially when their predecessors were white. They also report less acceptance and support from staff, especially those with white predecessors.7 And, based on their life experience, they may feel underpaid as well as underappreciated.

Board members can support these leaders by encouraging bold vision, supporting financial decision-making for long-term success, and championing the work. Strengthening support systems and fostering strong relationships between boards and leaders of color are essential steps toward building greater organization resilience and addressing critical areas for improvement.

Learn the Business

Understand the organization’s financial condition, context, how the business model

works, and what metrics are important to monitor.

A nonprofit’s business model refers to how it makes and spends money in service of its mission. A sound business model is comprised of expense management and the securing of diverse, reliable, repeatable, and replaceable revenue sources. A nonprofit’s balance sheet shows its capital structure – what an organization owns (cash, receivables, investments, property, and equipment); what it owes (payables, debt, deferred revenue); and what’s available to support the mission (net assets with and without restrictions). Ensuring a resilient business model starts with answering three questions:

- Is the organization living within its means?

- How might operations change during a crisis?

- What changes can the organization make to continue living within its means?

While revenue streams come and go and expenses change, the goal of the business model is to generate enough revenue to exceed expenses and ideally achieve a surplus.

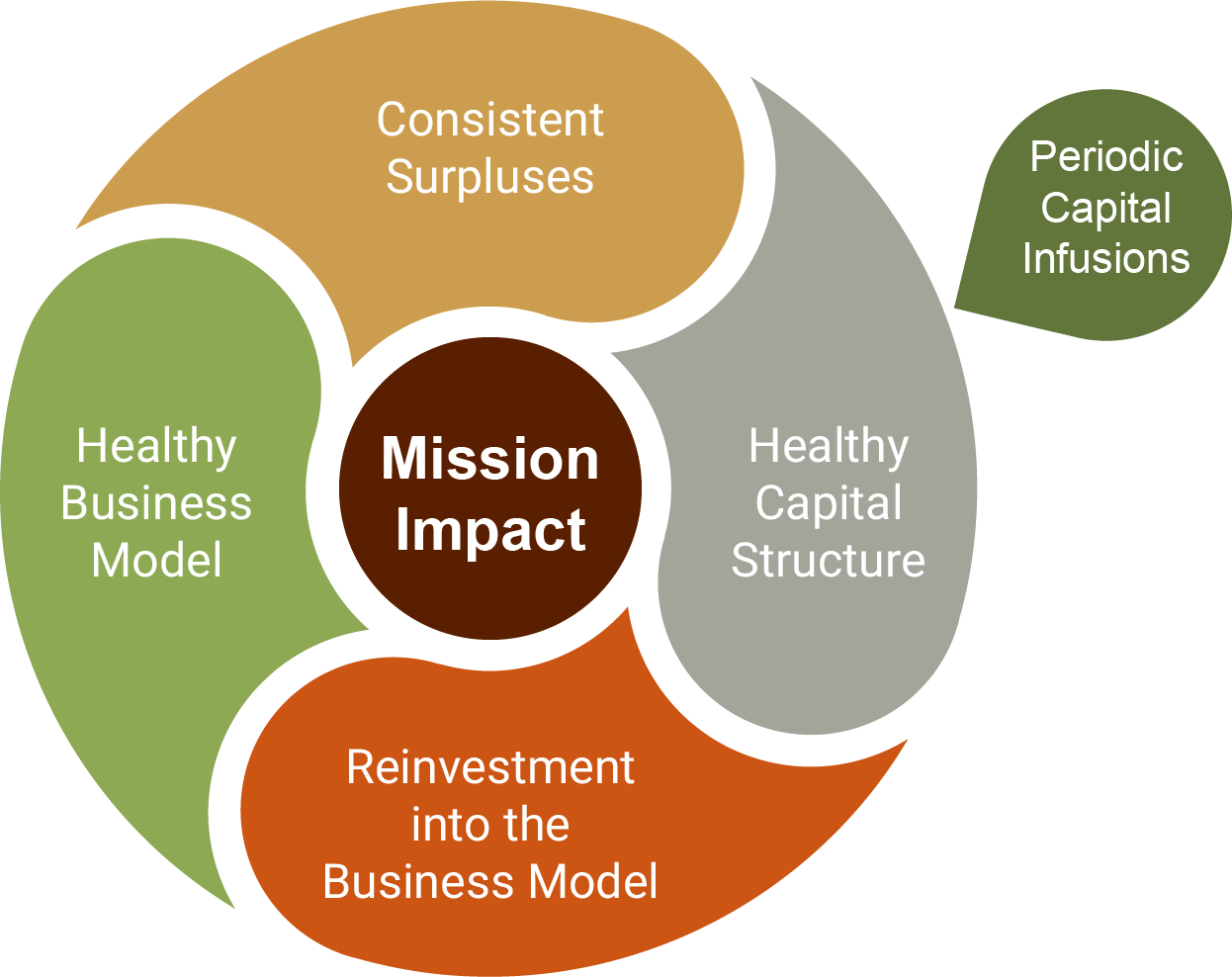

FIGURE

Comprehensive-Financial-Health

Nonprofit staff, board members, and funders should be aware that budgeting to a surplus is crucial to the financial health of nonprofits “Nonprofit” is a misnomer in that it defines how an organization is treated under tax law but does not accurately reflect the reality that nonprofit must generate revenue to invest in their missions and sustain themselves financially. Surpluses provide nonprofits with flexible, adaptable resources to reinvest back into their business models (programs and services) and to grow, expand, change, or adapt as needed. Many nonprofits operate with insufficient reserves and feel constant financial pressure. Generating surpluses provides the reserves and liquidity nonprofits need to mitigate risk and to support consistent and innovative programs, expand services, and invest in staff. Especially in today’s unpredictable financial environment, surpluses are a sign of good financial stewardship.

How nonprofits can generate surpluses:

- Aim to raise more revenue than is spent.

- Budget for surpluses annually, even in small amounts, to build an operating reserve.

- Diversify funding streams to include a variety of earned and contributed revenue opportunities.

- Invest surplus funds in financial instruments that maintain the nonprofit’s liquidity and have a favorable interest rate.

Defining the business model and capital structure provides the staff and board with:

- A clear picture of financial health.

- Benchmarks to monitor progress.

- A structure to manage finances and make data-informed decisions.

- Data to communicate needs to advance the mission.

- Opportunity to advocate and explain the full cost of the work.

What About Deficits?

Consistent surpluses are necessary, but not all deficits are bad. An organization with reserves will likely need to spend them down to cover a crisis, a program change, or a large one-time purchase. In such cases, running a planned deficit can be a sign of good financial stewardship. The key is for the board and staff to agree on the purpose of the deficit or surplus and to communicate their rationale and needs to funders, who may not understand that a break-even budget in an uncertain world can quickly become an unplanned deficit.

Facilitate an inclusive, equitable budgeting process

We characterize an inclusive, equitable budgeting process as a collaborative effort between staff and board members so that they can:

- Dedicate the time and space to meaningfully engage with financial information and weigh in on key decisions about revenue generation, including how it is spent on programs, services, and operations.

- Create a budget that reflects the organization’s commitment to its mission and meets the day-to-day operating needs

- Provide as much transparency as possible to help promote more informed conversations about organizational decision-making, program updates, and finance – particularly around staffing, salaries, equitable pay, and business model shifts.

- Build in review and feedback opportunities throughout the year that will allow for any adjustments needed to the original budget. This is especially important if actual funding is greater or less than anticipated.

Think Full Cost

Discuss how to plan for financial needs beyond the budget, such as reserves, working capital, and facilities.

A sustainable business model that provides reliable revenue to cover the full cost of doing business is crucial to a nonprofit’s ability to provide services effectively. The full cost of doing business goes well beyond simply paying for overhead; it includes investments in an organization’s immediate and future health. A full cost approach includes day-to-day operating expenses, both program and overhead, plus a range of short-term and long-term needs – including the financial resources it takes to run an effective organization for the long haul. Full cost needs vary by organization, but are understood as follows:

What All Nonprofits Need

- Total Expenses: The day-to-day direct and indirect, program and overhead, unfunded (not included in the budget), and underfunded (included in the budget but not at ideal levels) expenses.

- Working Capital: Cash to keep operations going strong, even when waiting for delayed contract reimbursements.

- Reserves: Money to navigate unexpected events, survive a crisis, or act on a new opportunity.

What Some Nonprofits Need

- Debt Principal Repayment: Money to pay back what’s been borrowed.

- Fixed Asset Additions: New equipment, buildings, and other fixed assets.

- Change Capital: Large, flexible dollars to reposition the business model.

Covering full cost is not an aspirational exercise. To become financially resilient, nonprofit leaders must acknowledge long-term operational and financial needs, and board members must evaluate financial health to include these needs. A full cost budget provides organizations with the data and framing to present current and future needs to funders.

How to have better full cost conversations

Use these questions to guide full cost conversations between staff and board members. Their answers will help clarify full cost needs and make a stronger case to funders for full cost funding:

Total Expenses: What is the full cost of each program? What are programs’ unfunded and underfunded expenses?

Working Capital: What is the cash flow pattern throughout an entire year?

Reserves: What amount would adequately protect the organization in the event of revenue losses? How many months would it take to enact a new plan?

Debt Repayment: What debt does the organization currently have? How quickly does the debt need to be repaid?

Fixed Asset Additions: What additional fixed assets are needed to support the organization and its mission? What will it cost to acquire these new fixed assets?

Change Capital: What change will the organization undertake? Why? What are the projected start-up (one-time) costs? Will this change or add ongoing costs to the expense base?

Monitor

Keep an eye on financial health through concise reports that help inform decisions.

Every board has its own culture and set of norms – both spoken and unspoken. Many board members feel pressure to maintain the status quo and help the decision-making process move expeditiously. For some, it can feel uncomfortable to pose questions to dedicated staff about the financial aspects of their work for fear that hard questions may imply a lack of trust in leadership. But board members must ask hard questions to make well-informed decisions.

Because all nonprofits are different, there is no single approach for how a board should exercise its fiduciary roles and responsibilities. However, there are a few essential practices that staff and board members can follow to help ensure financial resilience. For some organizations, the treasurer or finance committee plays an active role in educating the full board in this area.

While the details of these practices may be delegated to the finance committee, all board members should understand these ideas and participate in the monitoring process.

The board’s specific tasks should include:

- Monitoring budget against actual numbers at least quarterly.

- Updating projections when new information comes in.

- Ensuring adequate oversight of the audit relationship (if relevant).

- Committing to ongoing feedback loops and sharing the “why” behind decisions so staff and board members feel heard and valued.

For example:

The board is considering the possibility of sunsetting a well-loved, hugely popular program that operates at a deficit. The executive leadership and board chair share this news at a staff meeting. Staff express concerns about the impact of this change on program participants and how the community will receive the news. There are questions about staff layoffs and the cause of the operating deficit. Staff request 30 days to hold internal planning meetings to determine if there might be a way to salvage the program. The board chair agrees to hold a special meeting where the staff recommendations can be shared. The board also agrees to share their rationale for potentially sunsetting the program and the financial data that informs the conversation. The staff and board engage in a collaborative conversation about how to move forward and the board makes a commitment to provide staff with quarterly financial updates, so they stay informed.

Stay focused on your finance

Use these questions to monitor your budget and finances

During the budgeting process:

- Where is the greatest risk in this year’s budget? Which revenue streams are most uncertain, and what can be adjusted if they don’t materialize? Are there alternative funding sources? Could any expenses be minimized or put off until the following year?

- What is the process to monitor performance against the budget plan? Have the dates for review been put on the calendar?

Throughout the year:

- Is there a variance? If so:

- Is it due simply to revenue timing issues or is it unclear where the money will come from?

- What actions are needed to get back on track?

- Is there enough cash or reserves to cover current obligations?

- How long could the organization operate in an emergency?

- Are there unrestricted savings available to navigate risk?

Plan for the Unpredictable

Explore a range of possible outcomes and conditions that might influence financial health.

Nonprofits must use past financial performance, current trends, and a set of priorities to design a financial plan that reflects the dollars expected and how they’ll be spent throughout the fiscal year. But even with careful planning, unpredictable situations emerge, forcing staff and boards to pause, pivot, or make quick decisions under pressure.

Scenario planning is a useful exercise to explore “what ifs” and translate them into concrete possibilities, helping organizations make thoughtful, informed decisions when challenges arise. Scenario planning is also helpful when considering big decisions that could affect the business model, like choosing among several opportunities with limited resources or deciding whether to purchase a new facility. Ideally, this type of scenario planning happens before the next fiscal year but can be a helpful real-time exercise when unexpected circumstances arise.

A scenario planning process allows leaders and the board to:

- Consider what future conditions or events are probable.

- Identify what consequences or effects might exist.

- Establish potential responses or benefits

- Identify a range of outcomes to help make decisions.

Ultimately, scenario planning results in a set of options to help understand and prepare for various financial outcomes. Every part of the process is valuable.

Build a scenario plan

Review the budget.

- Check the underlying assumptions that

inform the revenue and expenses. - Ask: What scenarios informed the

budget projections? What variables

were considered? What’s missing?

Define the goal.

- Defining the goal will help focus conversations.

- Ask: Is a decision needed right now? Are there contingency plans for various possibilities?

Develop a narrative for each scenario.

- Talk through what will happen to staff, programs, revenues, and expenses under each scenario.

- Ask: What actions would be needed?

Build a financial model (if needed).

- If applicable, include indicators that might influence movement from one scenario to another.

- For example: If in Scenario A, X% of revenue doesn’t arrive by date Y, Scenario B now applies, and Z% of expenses must be cut.

Go Beyond Dollars and Cents

Tie decisions and actions back to mission and organizational health.

Money is crucial to running an organization, but conversations about resilience shouldn’t necessarily start with money. Operational and financial decisions must be informed by the organization’s vision, mission, and values, which in turn guide the organization’s strategy. Access to good information and a solid understanding of an organization’s performance is the bedrock of planning for the future, and it can’t be implemented without a strategy.

Leadership should create consistent opportunities for the staff and board to share their excitement about the work, the mission, and the value of the organization. These moments to pause, reflect, and share stories can both ignite a passion for the work and build trust. They help board members connect to the work, share their expertise, and more effectively serve in their governance and fiduciary role. Storytelling can unearth new insights and help build resilience. From there, staff and board can work together to:

- Engage in comprehensive financial analysis.

- Align business needs and funder dollars

to support the mission and vision. - Inform strategy for both mission and programs.

Identify your collective strengths

In the pursuit of resiliency, it’s important for nonprofits to recognize their strengths. Doing so during a staff or board retreat, committee meeting, or year-end celebration can solidify a sense of purpose.

This can be done through conversations or a survey or worksheet. Questions should include:

- People and Skills: What people, skills, and experiences are available to support business model changes and navigate challenges? How can staff’s skills and experiences be used to support the community?

- Financial: What financial investments are needed to build on the organization’s strengths?

- Data and Know-how: How does the organization impact the communities it serves? How can its data and knowledge benefit those communities?

- Relationships and Reputation: How does the organization “show up” in its community and what is it known for? What value does it bring to the communities it serves? Is the organization known as a good and reliable partner and collaborator?

The Stakes are High

The loss of vital organizations is a sobering reminder of the critical importance of strong

financial stewardship within the nonprofit sector.

Nonprofit board members and executive leaders must be champions of financial health, ensuring that their organizations can not only survive but thrive amid economic uncertainties. Leaders can safeguard the mission and impact of their organizations by embracing governance and fiduciary responsibilities, fostering financial literacy on the board, and encouraging transparent, equitable budgeting practices.

“Financial oversight is not just a task; it is a mission-critical function that allows nonprofits to serve their communities, both in times of need and for the long-haul as communities prosper with their support.”

The stakes are too high: Now more than ever, board members must engage proactively, collaborate with staff, and make informed decisions that prioritize sustainability, equity, and long-term success. Financial oversight is not just a task; it is a mission-critical function that allows nonprofits to serve their communities, both in times of need and for the long-haul as communities prosper with their support. And when oversight is inadequate, and an organization struggles or collapses, a deeply human cost is paid, both by the leaders and staff who delivered the services and the clients who depended on them.

Acting on the Vision

Nonprofit financial resilience requires leadership and the board working in concert toward a common goal. Financially resilient organizations can stay true to their missions even when pivoting to address unforeseen challenges. These guidelines help ensure that boards can exercise strong and informed financial management.

Foster a Collaborative Culture

Do: Engage in productive conversations about financial health, risk, and opportunity, giving staff time to prepare and address issues.

Don’t: Surprise and derail staff with new information.

Learn the Business

Do: Understand the organization’s financial condition, context, how the business works, and what metrics are important to monitor.

Don’t: Separate finances from programs, people, or impact.

Think Full Cost

Do: Discuss how to plan for financial needs beyond the budget, such as reserves, working capital, and facilities.

Don’t: Fear a surplus; nonprofits need surpluses to manage effectively for the long term.

Monitor

Do: Review financial health through concise reports that help inform decisions.

Don’t: Make decisions without knowing how they affect the mission and financial health.

Plan for the Unpredictable

Do: Explore a range of possible outcomes and conditions that might influence financial health.

Don’t: Ignore trend data, as it can be used, along with past financial performance

and priorities, to inform decisions in times of uncertainty.

Go Beyond Dollars and Cents

Do: Tie decisions and actions back to mission and organizational health.

Don’t: Focus on small issues or program-level decisions.

Additional Resources

- Download NFF’s scenario planning tool at learn-nff.org/scenarioplanning.

- For additional tips and tools, check out NFF’s budgeting resources at nff.org/fundamental/nonprofit-budgets-how-get-started.

- Learn more about full cost funding and find full cost tools at nff.org/full-cost.

-

Lisée, Chris and McGill, Larry. Nonprofit Finances Now. January 12, 2023. Stanford Social Innovation Review. https://ssir.org/articles/entry/nonprofit_finances_now.

-

A Candid study found 43% of majority BIPOC-led nonprofits had expenses under $50,000 and 25% had expenses above $1 million, compared with 16% and 40% of majority white-led organizations. It also found the median revenue of majority white-led organizations was 54% higher than that of majority BIPOC-led organizations. Uchida, Kyoko. What to know about U.S. nonprofit sector demographics. May 16, 2024. Candid. https://blog.candid.org/post/diversity-in-nonprofitsector-candid-demographic-data-report.

In addition, Echoing Green found that among the highest qualified applicants to its leadership development program, Black-led organizations had 24% smaller revenues. Dorsey, Cheryl, et al. Overcoming the Racial Bias in Philanthropic Funding. May 4, 2020. Stanford Social Innovation Review. https://ssir.org/articles/entry/overcoming_the_racial_bias_in_philanthropic_funding.

-

2022 State of the Nonprofit Sector Survey. (2022). Nonprofit Finance Fund. https://nff.org/file/1835/download?token=ZVahXV6E.

-

Sloane, Kelly. Reflecting Forward: Philadelphia-based Black Nonprofit Leaders’ Recommendations for Regional Funders. June 2022. https://unitedforimpact.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Reflecting-Forward_FINAL.pdf.

-

Fish, Susan. Dealing with difficult boards: Tips for executive directors. November 16, 2016. Charity Village. https://charityvillage.com/dealing_with_difficult_boards_tips_for_executive_directors/.

-

Jayasinghe, Tiloma. Women of Color Leaders: Shifting Power Dynamics within the Board–Executive Relationship. May 23, 2024. Nonprofit Quarterly. https://nonprofitquarterly.org/women-ofcolor-leaders-shifting-power-dynamics-within-the-board-executiverelationship/.

-

Thomas-Breitfeld, Sean and Kunreuther, Frances. Trading Glass Ceilings for Glass Cliffs: A Race to Lead Report on Nonprofit Executives of Color. (2022). Building Movement Project. https://buildingmovement.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Race-to-Lead-EDCEO-Report-2.8.22.pdf.