IN THIS ARTICLE

Leveraging Publicly Owned Land to Support Entrepreneurship and Affordable Housing Overview of the Land Disposition Process Analyzing the Current Process The Affordable Housing Challenge Case Studies Acting on the Vision Download PDFLeveraging Publicly Owned Land to Support Entrepreneurship and Affordable Housing

Currently, the City of Philadelphia has approximately 5,200 vacant parcels of land available for sale – a minimal change from the 6,300 recorded in 2019.1 Still, these figures do not include as many as 35,000 vacant and tax delinquent properties that remain in private hands.2

Considering the harm that vacancy and blight cause, especially in the lower-income areas where city-owned lots are most concentrated,3 this has become a growing concern for neighborhoods. Recent studies have found that remediating blight can reduce crime overall by more than 20 percent and violent crime specifically by as much as 29 percent.4

The city has begun to increase the pace of dispositions, having conveyed more than 400 parcels from January to May of 2023 — more than in any full year for which the city has published data.5 But more can, and must, be done.

Continuing to find ways to speed disposition of city-owned vacant property is a worthy goal in and of itself, given the downsides of vacancy. There is also great potential to do so while also leveraging the land to make progress on other important policy objectives, including wealth-building for small and Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) entrepreneurs and the development of affordable housing.

We urge city leaders to take measures to streamline the land disposition process, make that process more accessible, and to provide a more robust toolkit to help make the development of affordable housing on public land economically viable.

In this brief, we focus particularly on ways the city might improve the disposition of single parcels or small groups of parcels. We do so for two reasons. One is that these properties comprise a significant portion of what remains in the city’s portfolio. The other is that they represent the most promising opportunities to support small and BIPOC entrepreneurs.6

Specifically, we recommend:

- Reducing the amount of paperwork, review, and requirements for buying a single lot or small group of lots.

- Strengthening comprehensive planning at the council-district level, thereby empowering city staff to move more quickly on dispositions.

- Targeting affordability requirements and subsidies to neighborhoods at greatest risk of gentrification and displacement and enabling investment in neighborhoods where blight is a greater concern.

- Developing flexible new subsidies better suited to enable affordable housing development to occur across small-scale, scattered site developments.

All these efforts will require concerted focus from the next mayor. The experience of other cities shows that land disposition is a complex process that advances only with a strong champion in the mayor’s office.

But, city council has a vital role to play as well. In discussions about land disposition policy, so-called “councilmanic prerogative”7 — the practice of deferring the ultimate decision on the conveyance of any given parcel of land to the councilperson who represents that district — is often cited as a barrier to a faster, fairer process. There are certainly ways in which prerogative hinders disposition, but it also has an important role to play in ensuring that uses of public land align with highly localized public interests. Other cities have successfully improved their disposition processes while maintaining prerogative, and in any case, its existence is, and is likely to continue to be, a political reality. As a result, our focus is not on challenging the practice, but on finding opportunities for improvement within the existing policy framework.

Overview of the Land Disposition Process

Philadelphia disposes of land for development through both proactive and reactive channels, working primarily through the Land Bank.

The Land Bank proactively markets large parcels or groups of parcels through Requests for Proposals (“RFPs”) and individual parcels or properties through competitive sales processes. Developers can propose the purchase of other properties by making an application to the Land Bank, but only if those developers are already working with land around the property and need city land to complete the assemblage of a larger parcel, or if they are seeking to develop housing units of which at least 51 percent of which are affordable.

Developers can also access land through the Turn the Key program. Through this program, they develop homes for sales at up to $280,000 for first time homebuyers who are in turn subsidized by the city, and through the Minority Developer Program, which connects small BIPOC developers with technical assistance and facilitates the acquisition of city-owned parcels.

Across all channels, acquiring land from the City requires filling out a 39-page application, which seeks information on the intended use for the land, the financial wherewithal of the applicant to complete the project, and plans for any construction to employ registered Minority, Women and Disabled-Owned Enterprises (“MWDBEs”) and labor.

Applications are generally scored by city staff according to a rubric that gives specific weights to different considerations: 30 percent economic opportunity and inclusion; 15 percent public purpose/social impact; 20 percent development team experience and capacity; 20 percent financial feasibility; 10 percent project design; and 5 percent offer price. Where there is more than one bidder for land, the scoring is used to determine the winner. In instances where there is a single bidder, the scoring is used to help understand the ways the project aligns with – or strays from –the city’s policy and economic priorities. There is no minimum score a project must meet, but an application that scores lower than previous successful bids on similar properties will have more difficulty getting approved.

Most applications are unsuccessful. In 2022, 407 of the 696 applications submitted, about 58 percent, were denied.8 Successful applicants receive an agreement that entitles them to buy the subject land — after they secure any necessary zoning changes and permits and prove they have the financing necessary to pay for the work.

After the award of a property is made, city staff continue to review the project at multiple points as it goes through zoning and permitting, and they may request more information or plan changes. The final conveyance comes at the end of this process and must be approved by city council. From beginning to end, the process typically takes 12-18 months.

The bulk of successful dispositions for development have been through the RFP process. Since dealing with RFPs can be complex and time consuming, city staff tend to use them for large parcels or groups of parcels. For instance, in 2022, the city put out 21 RFPs seeking to dispose of more than 500 parcels, with the smallest assemblage being 8 parcels, the largest 86 and the average 26.

Analyzing the Current Process

This system is, in effect, the expression of several policy priorities. These include generating affordable and workforce housing; promoting equity for BIPOC developers, contractors, and workers; giving priority access to land for existing community members; reducing blight by disposing of as many properties as possible; and making sure land usage aligns with the public interest.

The ability of city and council staff to deliver on those priorities, some of which may conflict, hinges on their ability to control disposition and subsequent development. There have been high-profile incidents of city land going to speculators who have failed to put it into productive use, or have changed the intended use after taking control. These instances represent both policy failures and political embarrassments, and city leaders have directly tied the rules imposed on the disposition process to the objective of avoiding them in the future.12

Ultimately, this process has had unintended consequences. In particular, the complex and lengthy disposition process puts the onus on applicants to pay for a range of predevelopment activities —including design, environmental, permitting, legal, and other work — long before knowing that they own the land in which they are investing. This is a challenging position for any developer, and particularly so for small firms or non-profits with more limited resources.

“The complex and lengthy disposition process puts applicants in the position of having to pay for a range of predevelopment activities before knowing they own the land in which they are investing. This is a challenging position for any developer, and particularly so for small firms or non-profits.”

The city’s understandable focus on RFPs for larger parcels and assemblages has exacerbated the challenges for smaller developers; they simply do not have the capital or capacity to win land through this channel. In fact, public records suggest that the same small handful of larger developers have won RFPs repeatedly.

Likewise, blanket affordability requirements create more substantial hurdles for small developments — and the smaller developers undertaking them — than they do for larger ones. Anyone seeking a single parcel to develop as a rowhouse effectively must adhere to affordable guidelines for that unit to meet the 51 percent rule, and the math remains difficult for duplex and triplex development as well.

These outcomes are problematic for several reasons.

First, multiple current and former officials associated with the Land Bank noted that the bulk of large parcels and agglomerations have already been sold. Individual lots and small groupings of parcels represent a significant share of what remains,13 so relying on agglomeration to produce economies of scale is a strategy that may be reaching the limits of its utility.

Second, the multiple barriers to access for small developers is especially troubling in the context of the underrepresentation of people of color in the real estate industry. A recent study showed that fewer than 1 percent of real estate developers nationally are people of color. And those BIPOC developers that do exist tend to be small; of the 383 developers with revenues that exceed $50 million identified in the study, none were people of color.14 Particularly to the extent that BIPOC entrepreneurs are disproportionately represented among the ranks of smaller firms, the design of the current system undermines its own inclusion goals.

Philadelphia has a burgeoning ecosystem for BIPOC developers, with support programs like The Growth Collective and The Black Squirrel Collective, as well as the city’s own Minority Developer Program, offering training and access to capital to help developers start and scale. These programs exist because the real estate industry represents an important potential pathway to wealth creation. Yet, in interviews with participants in these groups, the city’s land disposition process was repeatedly cited as a hindrance, rather than a source of support.

The Affordable Housing Challenge

Leveraging publicly owned land to help create affordable housing is a paramount concern; it is the context in which uses for public land is most often discussed.15

There are limits, however, to how much can be accomplished simply by activating the city’s vacant property for the construction of affordable housing. The costs of building are such that even if a lot is given away for free, it cannot be sold or rented at especially affordable prices.

There are ways to improve this math. In larger-scale, mixed-income developments, higher-priced units effectively subsidize the lower cost units — though typically this approach yields moderately priced units, like the one in the example below, rather than ones affordable for the lowest-income Philadelphians. It is also possible to further subsidize development, with grants making up for the shortfall in proceeds from sales or rents.

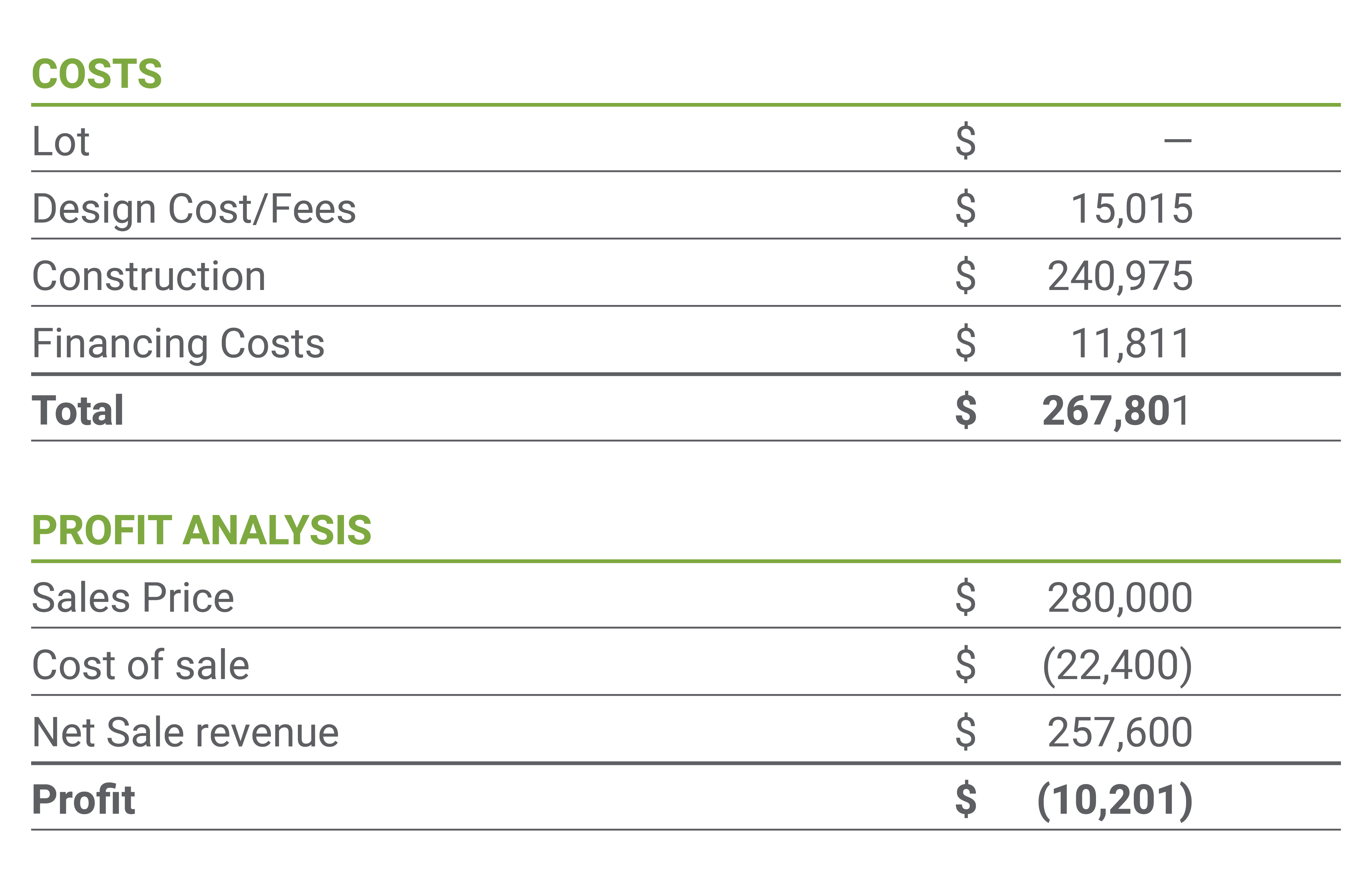

Financial Overview

Figure 1 shows that the economics of building a typical rowhouse to be sold at the $280,000 price point that the city has targeted for its “workforce housing.”16 Even with free land from the city, as this example assumes, the numbers simply don’t work. Costs would be roughly $268,000 and net revenue from the sale roughly $258,000 — a net loss of about $10,000. Still, even a $280,000 price point is unaffordable for many Philadelphians.

FIGURE

Sample Rowhouse Development on Subsidized Land

“The costs of building are such that even if a lot is given away for free, it cannot be sold or rented at especially affordable prices.”

These options, however, face significant barriers.

As noted above, the opportunities for achieving economies of scale using large lots or assemblages may be limited simply due to the remaining composition of the city’s portfolio.

Additionally, finding subsidy for smaller scale projects is challenging. The city’s existing subsidy programs primarily support larger developments. For example, in its most recent annual report, the city’s Housing Trust Fund cited 18 developments to which it had recently provided subsidy. The smallest was 20 units, and the average size was more than 50 units.17 This is a function of both the city’s efforts to maximize the number of affordable units it supports and the design of most subsidy programs, which come with compliance requirements that are difficult to manage on small projects.

The city’s recent creation of the Turn the Key program and Accelerator Fund are both promising steps toward subsidy programs that work at a smaller scale. Turn the Key can be used to support modest clusters of rowhouse development — generally 10 units or more at a time. The Accelerator Fund can support small (sub-four unit) multifamily projects and focuses on financing BIPOC developers. Still, neither is flexible enough to finance individual rowhouse development or to support deep affordability (below 60 percent of area median income) in most instances.

In short, without an evolution of the city’s subsidy resources, its vacant property portfolio on its own is unlikely to generate large quantities of affordable housing, and especially deeply affordable housing.

Case Studies

Philadelphia is far from alone in confronting challenges in its efforts to dispose of its vacant land and leverage it to achieve its policy goals. Many other cities have faced similar circumstances, and can offer valuable lessons.

Cleveland:

The Value of Simplified Processes Sensitive to Scale, and Strong Leadership

Among midwestern cities hard-hit by deindustrialization over the last several decades, Cleveland has had uncommon success in managing its vacant property inventories. In the early 1990s, the city created a land bank that won the 1993 Innovations in Government award for what the director of the city’s consortium of Community Development Corporations called “a remarkable revitalization stream” of properties for reuse. By 2003, the city had disposed of almost 6,000 buildable lots and only 1,000 remained on its books, with local non-profit developers noting in testimony to the city council that “the land bank was running out of land.” The bulk of the disposed land was redeveloped as housing — a mix of affordable and market rate units.

In a study on Cleveland’s disposition program, the University of Michigan’s Margaret Dewar, professor emerita in the Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning found that a streamlined disposition process was key. Perhaps most crucially, its land bank set uniform fixed prices for non-buildable lots and small buildable lots, while requiring appraised values for larger lots and commercial properties.

While each property sale ultimately required approval from the city council, so many of the terms and conditions were set out up front, especially for smaller properties, that a robust variety of developers (including small community-based non-profits) chose to participate.

Another crucial element, according to Dewar, was clear leadership. Two successive mayoral administrations explicitly prioritized land disposition as a vehicle for community and economic revitalization, empowering their departments to set up efficient processes to facilitate the work and negotiate with city council to achieve timely dispositions.18

It is worth noting that the importance of centralized leadership is a consistent theme across successful efforts to manage public portfolios of vacant property. While he took issue with other elements of the New York City’s approach to its vacant portfolio, then-Controller Scott Stringer noted in a 2016 study that successive administrations had prioritized returning the city’s vacant properties to productive use and had succeeded in reducing the more than 100,000 properties it had owned in the mid-1990s to fewer than 1,000 two decades later.19

Baltimore:

The Importance of Flexible Subsidy for Scattered Site Development

Baltimore has more than 14,000 vacant properties, 1,200 of which are city owned. As in Philadelphia, many of those are single parcels or small groups of lots that the city hopes to redevelop as affordable housing.20

As part of this effort, the city created a new block grant for scattered site affordable housing development. It provides developers/recipients with a fixed amount of capital that they can apply flexibly across multiple projects so long as they achieve minimum production and affordability levels across their portfolios. This allows them to manage the grant differently for different property types and scales — more subsidy for a single family rowhouse or deeply affordable unit, less for mixed-income multifamily properties that offer economies of scale and opportunities for internal cross-subsidy. Compliance and reporting requirements that might be unwieldy were the subsidy awarded on a more traditional property-by-property basis are manageable when spread across multiple small projects.

One of the first awards under this new program went to the Aequo Fund, an initiative that provides capital and training to participants it calls “Founders” — aspiring young people of color, women, and immigrants seeking careers in development (Aequo was started by Ernst Valery, one of the authors of this paper). The grant provided Aequo $2 million with the requirement that it be used to create a minimum of 25 housing units on formerly vacant and blighted properties that would be affordable to families making no more than 300 percent of the federal poverty guideline.

Aequo has begun to deploy the funds across multiple property types, including single family rowhouses and duplexes. The construction of duplexes, which are more cost-efficient than rowhouses, has allowed Aequo to create more than half its target number of affordable units while utilizing less than a quarter of the grant. Moving forward, this means Aequo will have funds to use to more deeply subsidize highly affordable units or build a total of more than the 25 unit target, early evidence of the value the program’s flexibility offers.

Acting on the Vision

To a significant extent, the city’s approach to its vacant land — from the disposition process itself to the subsidy sources that routinely run alongside disposition to generate affordable housing — is constructed around its larger properties and assemblages. While there are certainly shortcomings with that process, it makes the most sense for these holdings. Large-scale land uses have large scale-community impact, so they should be subject to robust review and compliance regimes.

The existing framework makes less sense for smaller lots and assemblages. In some instances, the guardrails the city put in place for large dispositions actually counter its own objectives for using city land to support BIPOC entrepreneurs. In any case, these smaller parcels now comprise a substantial portion of what remains in the city’s portfolio, which signals a need for new processes and tools to move them more efficiently and to better align their use with its policy objectives.

Develop a separate process for small lots and assemblages.

There should be fewer restrictions on the acquisition of single lots and small parcels than on large parcels, allowing such sales to proceed more quickly. For these properties, the city might consider:

- Reducing the volume of information required upfront.

- Reshaping ongoing compliance requirements during and after construction, including MWBE contracting and hiring requirements.

- Allowing acquirers to take possession of lots more quickly, perhaps in advance of full plan and permit approvals, and before evidence of full financing is in place. This would have to be accompanied by better enforcement of reversionary clauses that allow the city to take back properties from developers who fail to start work within a reasonable timeframe.

Capitalize on mayoral leadership to enable district-level planning.

The next mayor should actively partner with city council to further reform the city’s approach to its vacant portfolio. By prioritizing the issue in public fashion, the next mayor can put more pressure on the system to deliver results. In particular, the administration might seek to engage district councilmembers in comprehensive planning processes around the vacant land in their districts, including opportunities to “prequalify” small lots that can be disposed for agreed-upon uses without going through lengthy individualized approval processes.21 Such processes might even contemplate making zoning changes to further policy goals — for example, allowing by-right duplex or triplex development in some locations to encourage affordable rental production.

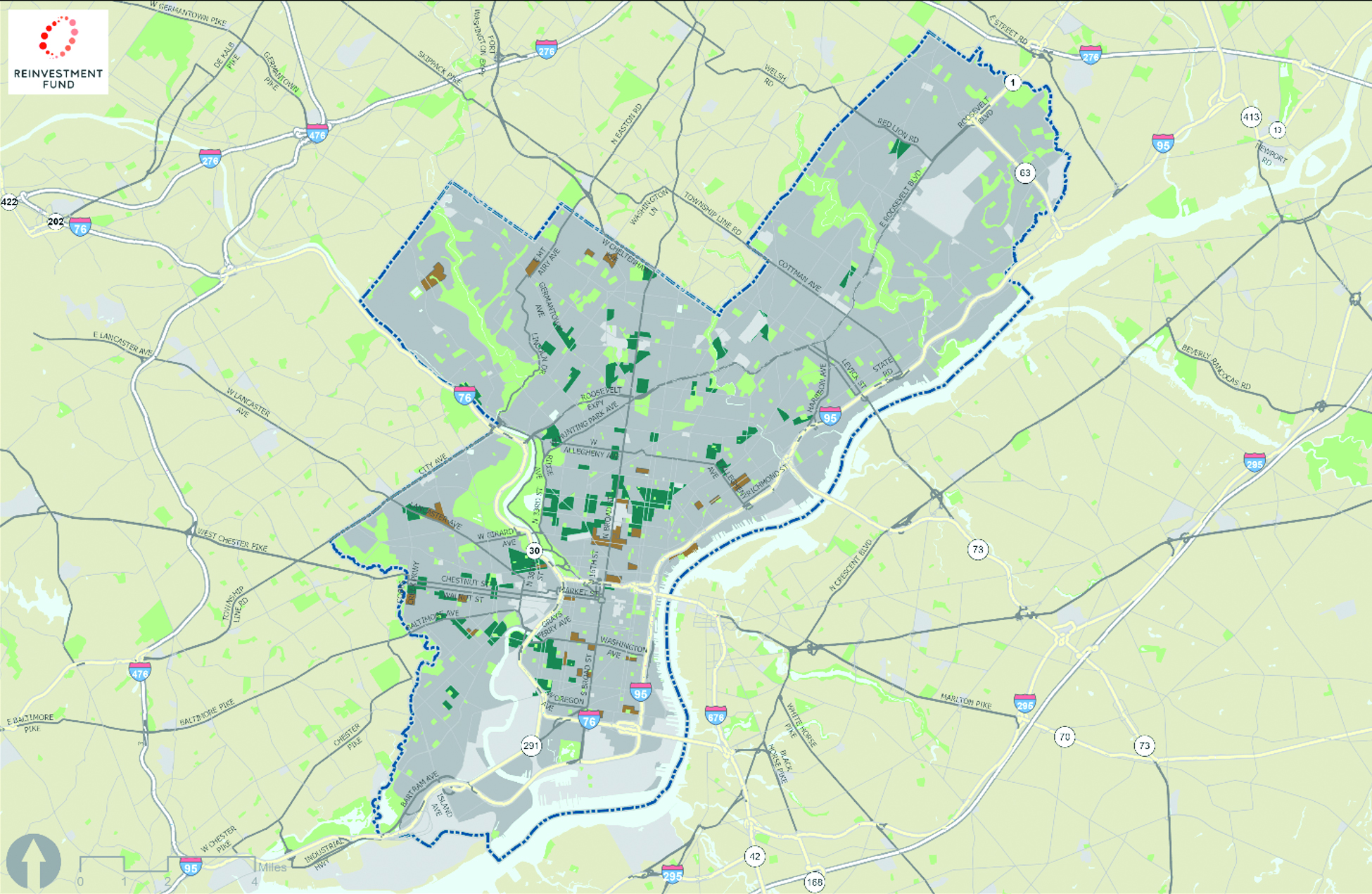

Acknowledge that different neighborhoods have different needs and use data to help guide planning.

The citywide guidelines that currently govern land disposition focus heavily on countering gentrification and creating affordability. In many neighborhoods, these are appropriate priorities; in others, disinvestment and blight might be more important to address. Reinvestment Fund’s Displacement Risk Ratio Analysis (Figure 2 below) provides an indicator showing where gentrification pressures are increasing, decreasing, or holding steady. In neighborhoods where such pressures are increasing, reserving the bulk of land for affordable housing and targeting deep subsidies to accompany that land makes sense. In other neighborhoods, pushing for faster utilization of vacant properties might be more advisable.

FIGURE 2

Green

Notable Increase in Displacement Risk Ratio – Housing prices are rising faster than incomes of existing residents, which could signal the onset of displacement.

Brown

Notable Decrease in Displacement Risk Ratio – Housing prices are not keeping pace with the incomes of existing residents, which could signal the onset of disinvestment.

Build new subsidy products that better leverage the city’s land portfolio.

These products should be able to efficiently support projects under 10 units, ideally as few as one or two. Oversight and compliance costs associated with the subsidy should scale up and down with the size of the project. Similarly, the subsidies should be flexible enough to adapt to different kinds of projects and levels of affordability. Making more resources available to the existing programs that already support this work, including Turn the Key and the Accelerator Fund, would also be useful.

If the city can improve its handling of its existing vacant portfolio, that would be a significant accomplishment, allowing the more efficicent disposition of small parcels and letting its land be a catalyst for affordable housing and wealth building among small, and especially BIPOC, entrepreneurs. It would also build support for even more ambitious efforts to reduce blight citywide and move beyond vacant parcels to problems like vacant structures, which offer their own raft of challenges and opportunities.

This paper benefited from insights from more than a dozen local practitioners, including current and former officials associated with the Land Bank and City Council, as well as for-profit and non-profit developers who have sought City-owned land, and housing policy advocates. It also had the support of a wonderful team of editors, including Larry Eichel and Elinor Haider of the Pew Charitable Trusts, Caitlin O’Brien of the Scattergood Foundation, Lauren Stebbins of the Barra Foundation, and Ellen Hwang. The authors are grateful to all those who contributed.

-

City of Philadelphia Department of Planning and Development. (2023) Land Management Dashboard. https://www.phila.gov/departments/department-of-planning-and-development/about/our-results/land-management-dashboard/

NOTE: City government owns additional vacant lots it is reserving for future use, and other public entities also own substantial volumes of vacant land. In this paper, we focus on the land owned by the city and available for disposition.

-

City of Philadelphia. (2019). Philadelphia Land Bank: Strategic Plan and Performance Report. https://k05f3c.p3cdn1.secureserver.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/2019_StrategicPlan_DRAFTREPORT_PublicRelease_060519_PRINT-6.5.19-REDUCED.pdf

-

City of Philadelphia. (2019). Philadelphia Land Bank: Strategic Plan and Performance Report. https://k05f3c.p3cdn1.secureserver.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/2019_StrategicPlan_DRAFTREPORT_PublicRelease_060519_PRINT-6.5.19-REDUCED.pdf

-

Love, H. (2021). Want to reduce violence? Invest in place. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/research/want-to-reduce-violence-invest-in-place/

-

City of Philadelphia Department of Planning and Development. (2023) Land Management Dashboard. https://www.phila.gov/departments/department-of-planning-and-development/about/our-results/land-management-dashboard/

-

NOTE: We do not address other, non-development uses for vacant properties, like community gardens and side lots, here – not because they are unimportant, but rather because they are simply outside our expertise and the scope of this paper.

-

Dewar, M. (2009). Center for Local, State, and Urban Policy: University of Michigan. Disposition of Publicly Owned Land in Cities: Learning from Cleveland and Detroit. https://closup.umich.edu/research/working-papers/disposition-publicly-owned-land-cities-learning-cleveland-and-detroit

NOTE: Cleveland, for example, maintained an almost identical form of prerogative while going through an otherwise complete overhaul of its disposition processes.

-

City of Philadelphia Department of Planning and Development. (2023) Land Management Dashboard. https://www.phila.gov/departments/department-of-planning-and-development/about/our-results/land-management-dashboard/

-

NOTE: Philadelphia does not publish data on the length of the disposition process. This figure is drawn from interviews with officials involved in the process and individuals who have acquired land from the city.

-

NOTE: The city does not publish specific data on this point; this conclusion is based on multiple interviews with officials involved in the disposition process, as well as indicative data the city does publish showing the affordability levels and pricing associated with dispositions.

-

PHDC. (2023). Making Philadelphia Better Block by Block: Previous Development RFPs. https://phdcphila.org/rfps-rfqs-sales/development-rfps/previous-development-rfps/

NOTE: This data is based on an analysis of historic RFPs

-

Bender, W. (2018) Following a $165K windfall, Kenney cracks down on public land flipping. The Philadelphia Inquirer: https://www.inquirer.com/news/mayor-kenney-philadelphia-vacant-land-flip-vprc-20181210.html

-

NOTE: This finding is based on interviews with more than a half dozen current or former administration and council staff members, Land Bank board members, and others with direct knowledge of the City’s vacant property portfolio.

-

Coleman, C. (2023). Black and Latino Real Estate Developers Struggle to Get Funding. The New York Times: https://www.nytimes.com/2023/03/03/realestate/real-estate-developers-black-latino.html

-

Moselle, A. (2023). Philly mayoral candidates on affordable housing, vacant land. WHYY: https://whyy.org/articles/philadelphia-mayor-election-affordable-housing-vacant-land/

-

NOTE: Unlike larger-scale construction, there is little quality data on rowhouse construction costs.The figures here are compiled from the collective experience of the authors and was based particularly on transaction data from Spring Garden Capital Group, which has financed over 1500 housing units in the City of Philadelphia over the last five years.

-

Philadelphia Housing Trust Fund. (2021). Expanding Housing Opportunities & Revitalizing Neighborhoods. Philadelphia-Housing-Trust-Fund-Report-2020-2021.pdf

NOTE: Assumptions include: a 10 percent down payment, a 30-year mortgage at 6 percent interest, $720 in annual insurance and $1,200 in annual property taxes

-

Dewar, M. (2009). Center for Local, State, and Urban Policy: University of Michigan. Disposition of Publicly Owned Land in Cities: Learning from Cleveland and Detroit. https://closup.umich.edu/research/working-papers/disposition-publicly-owned-land-cities-learning-cleveland-and-detroit

-

Office of the New York City Comptroller. (2016). Building An Affordable Future: The Promise of a New York City Lank Bank. https://comptroller.nyc.gov/wp-content/uploads/documents/The_Case_for_A_New_York_City_Land_Bank.pdf

-

Mayor Brandon M. Scott: City of Baltimore. (2022, March 11). City’s Review of Vacant Properties Complete, Mayor Announces $100 Million ARPA Commitment Towards Housing Equity [Press Release] https://mayor.baltimorecity.gov/news/press-releases/2022-03-11-city%E2%80%99s-review-vacant-properties-complete-mayor-announces-100-million

and

City of Baltimore. (n.d). Buy Into Baltimore https://buyintobmore.baltimorecity.gov/

-

NOTE: While there has not been a formal practice of joint district level planning between administration and council staffs, Council President Clarke, Councilman Kenyatta Johnson, and former Councilwoman Maria Quiñones-Sánchez have been especially focused on the concentrations of city-owned land in their districts—the Fifth, the Second, and the Seventh—and have seen the largest volume of dispositions in recent years as a result.